Leo Braudy is Leo S. Bing Chair in English and American Literature at the University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Every year at the Oscars, the cameras pan to the famed Hollywood sign and its bold white letters.

Ask someone today what the sign symbolizes, and the same words will likely crop up: Movies. Stardom. Glamour.

But as I point in my book on the Hollywood sign, the sign didn’t always represent fame and fortune. As the city changed, so did the meaning of the sign, which, at one point, was even considered a public nuisance.

Come to … Hollywoodland?

California has long possessed the lure of material and personal fulfillment.

What started as a destination for those hoping to strike gold became, in the late 19th century, a mecca for anyone with real or imagined ailments. The state’s temperate climate and natural springs, guidebooks claimed, possessed “restorative powers for weakened dispositions.”

The state’s gold has since been drained, and the quest for perfect health has spread to rest of the country. But the erection of the famed Hollywood sign in 1923 marked the start of another phase, one still with us today.

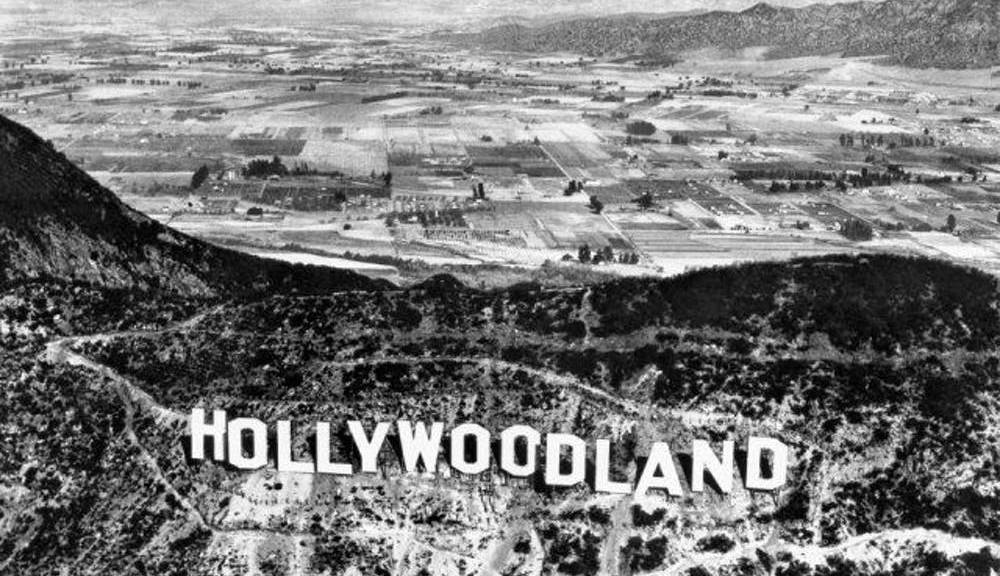

During that decade, a real estate development group, one of whose principal backers was Los Angeles Times publisher Harry Chandler, built a large sign – essentially a billboard – on an unnamed mountain between the Los Angeles basin and the San Fernando Valley.

“Hollywoodland,” the sign read. Its 40,000 blinking light bulbs advertised a new housing development built to accommodate the city’s surging population, which more than doubled during the 1920s to become the fifth largest in the country, as the city drew people from all over the country for its weather, open spaces and jobs.

The city of Hollywood had been absorbed into Los Angeles only a decade earlier. At the time, it was a wealthy area that had grudgingly accepted the movie business. Many mansions dotted the hillsides below the sign, and utopian communities like Krotona, the U.S. headquarters of a mystical organization called the Theosophical Society, had sprung up in the foothills and on the flats.

Accordingly, early advertising for Hollywoodland emphasized the development’s exclusivity. It would offer an escape from the smog, dirt and unwelcome neighbors of downtown Los Angeles.

Saving the sign

Because the sign holds such a prominent place in the nation’s cultural imagination today, it may be surprising to learn that it wasn’t until fairly recently that it achieved its iconic status.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the sign makes an appearance in only a few of the movies that were about Hollywood or the movie industry. Other Hollywood institutions, like the Brown Derby restaurant, tended to represent the film world.

In the 1940s, Los Angeles – as both city and symbol – started to change. A dense smog settled over the metropolis, which would be featured as the grim, shadowy setting of noir films like “The Big Sleep” and “Double Indemnity.”

The sign – a little dingier, a little more unslightly – reflected the changing city. Since it was originally intended as an advertisement, few had considered its permanence or long-term significance.

The hillside where it had been built was dangerously steep; workers had cut the letters from thin sheet metal, which they tacked onto telephone poles. Heavy winds could easily rip the letters away, and by the late 1940s, there had been so much deterioration that the city of Los Angeles proposed to tear it down, calling it a dangerous public nuisance.

Color photo of the Hollywood sign with blue sky above

The Hollywood Sign after a 2005 refurbishment (Photo by David Livingston/Getty Images)

That dismissive view of the sign began to change in 1949, when the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce told the city that it would take over its ownership and maintenance. With that exchange, the “land” suffix was dropped. We could say that this is the point that the Hollywood sign we know today was actually born.

However, improvements and maintenance occurred in fits and starts. By the early 1970s, committees were being formed to “save” the sign in order to restore it beyond shoddy paint jobs and patchwork repairs.

Finally, in 1978 a committee headed by Hugh Hefner and Alice Cooper collected the funds – about $27,000 per letter – to not simply repair, but rebuild the sign.

Today the big white letters are a permanent fixture in the Los Angeles landscape, and it’s even withstood the attempts of adventurous vandals to emulate the art student who, in 1976, tweaked the sign to read “Hollyweed.”

The ConversationIn their own way, these vandals are trying to carve out their own slice of the Hollywood dream – a quest not for gold or for health, but for recognition and fame, whether by talent, ambition or selfie.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation, an online publication that features academics writing about their research and ideas for the public. KQED and The Conversation are partners in the California Dream project, a collaboration looking at the Golden State’s promise, whether we are achieving it, and the future of California.